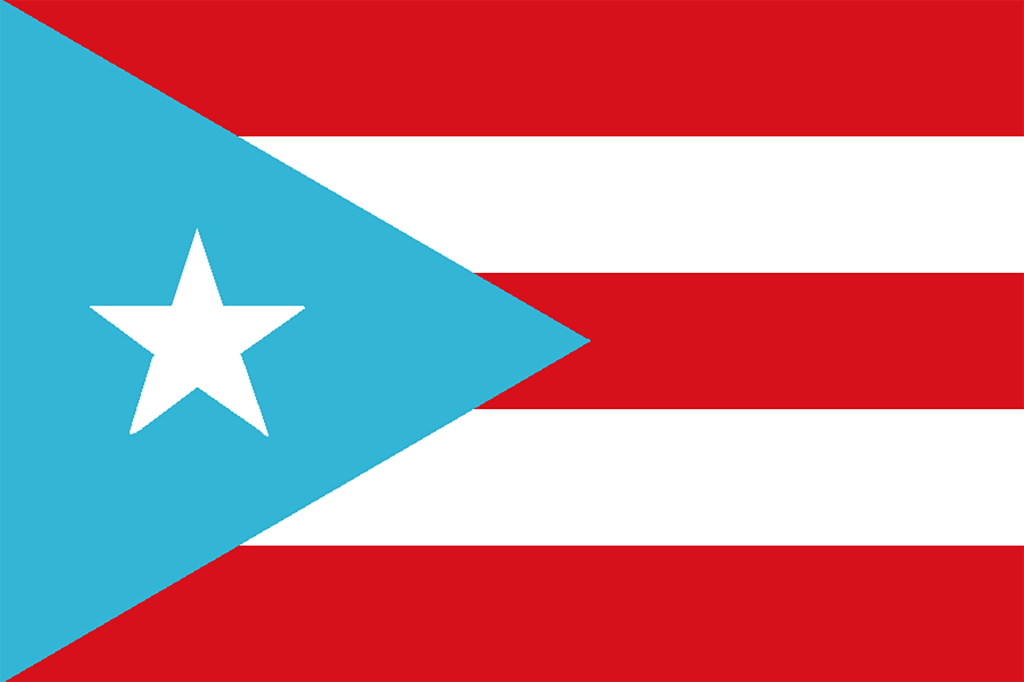

JULIANNA PADILLA

21 YEARS OLD, DAUGHTER OF PUERTO RICO

Before I became an older sister, I was an independent and spoiled toddler. My father, a combat medic in the Army, had been deployed to Iraq for the first year of my life, leaving my mother to juggle being a first-time mom and a night-shift nurse. She often jokes about how, sometimes, she was so tired that she would fall asleep on the couch next to my playpen and wake up when I gently patted her arm and asked for lunch. I was kind, never cried, kept to myself, shared my toys with other kids, and was a pretty calm toddler.

I was 2½ when my sister, Gabby, was born. Around the age of 6, it became my responsibility to get my sister ready for the day. On weekends, I’d feed her and keep her entertained while my parents slept. My mom likes to joke that I even potty-trained my sister when I was 4.

I’m not only the firstborn child. I’m also the first niece and granddaughter. I have spent my entire life picking up everything and piecing it back together for my family. Suppressing my emotions and remaining as calm as I could manage to meet the standards my family held me to. I became a secondary parental figure for my sister and cousins for as long as I can remember, while endlessly trying to impress my elders.

As I got older, my responsibilities became more taxing, especially with me developing a classic Type A personality.

When I was in high school, my dad gave me the nickname The Secretary. If my family were going to a party, the invitation would go to me, The Secretary, to plan everything. I would buy and wrap the gift, sign the card for all of us, and even plan everyone’s outfit. On top of doing chores around the house, I became the “family therapist” and was always trying to fix everyone’s problems. I could only do so much other than carry around those burdens and keep quiet after they all swore me to secrecy. I tiptoed around their high-volume emotions and tried to play peacekeeper because the one job I ever felt I was truly made for was a moderator for my family.

Even now, I struggle to balance living at home and college life. My mom still turns to me to keep my sister in the loop with family doings and help her with school, even though she’s 19 now. I’ve helped Gabby and, so far, four cousins through the college application process, which nobody held my hand through. There have been so many times when I had to figure things out on my own. I’d see my friends’ parents and families guiding them through everything, and feel so alone.

After having discussions with friends and hearing stories of struggling Latina eldest daughters on social media, I realized that this was more common than I thought. I discovered #eldestdaughtersyndrome on TikTok in early 2023. The hashtag is filled with videos of feminine rage, storytelling, memes, and lots of crying about being robbed of a childhood after assuming so many domestic roles at too young an age. In one video posted by @sarahthebookfairy, she says, “This one’s for the eldest daughters – what do you think it’s like to not constantly be aware of the emotion of every single person around you and make it your responsibility to always make sure that everyone is okay, no matter what energetic, emotional, or mental toll it takes on you? I imagine it’s pretty nice!” My younger sister sent me this video. She said, “This is so you LOL.”

In her master’s thesis “The Effects of Being the Oldest Daughter and a Caretaker,” social worker Sahira Gonzales writes, “Within the Latino cultures, there are expectations placed on the oldest daughter to place their needs second to those of their family and household activities that support the family. These beliefs are the creation of the concept of familia that states family members are meant to be united, who dedicate and uphold responsibilities that support the family, more strictly on female members to be the good daughter.”

Like many other young Latinos, I have heard a million times over about the importance of pursuing a career in medicine. My mother is a nurse, my father was a combat medic in the Army, my aunts are nurses and physician assistants, my abuela was a dental hygienist and then went on to work in environmental, my abuelo was a certified nursing assistant, CNA, and I have uncles who are in radiology and medical transport. They told me about the financial security and the “pendulum” of always needing doctors and nurses. But after my family found out how queasy blood makes me, they knew I didn’t have the stomach for medicine.

Kaylin Sevilla-Lopez, a 22-year-old pre-med student at Hunter College, joked about her family pushing her to be a doctor, lawyer, or engineer. “They’ll glorify you if you become a doctor — because if you’re not a doctor, no sirves, para nada.” Meaning, you’re useless, good for nothing.

All jokes aside, the lack of Latinos in healthcare has always interested me, especially since I have so many family members in the field. In a 2021 analysis of federal government data, the Pew Research Center found that only 9% of the nation’s health care practitioners and technicians are Hispanic, compared to the total of 9,796,854 people working in healthcare currently. Pew found that only 7% of all U.S. physicians, surgeons, and registered nurses are Hispanic. According to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 6.9% of the registered nurse workforce is Hispanic/Latino.

Over the past few months, I’ve had discussions with Latinas who are striving toward careers in medicine, working in medicine, and retired from medicine. I went into this project to see if the stress carried throughout the eldest daughters generationally and culturally. To hear the voices of women who have given themselves and their childhood up to serve the needs of others, their entire lives. To see how patriarchy, machismo, and gender roles still thrive, and how Latinas are taught to grin and bear it all.

I had one goal in mind: creating a community of eldest Latina daughters. I felt relieved when speaking to women who struggled their whole lives with being heard or suppressed. There were a lot of shared experiences, memories, and laughs. We talked about having to stay close to home for college, navigating familial disappointment, and the pressures of being a woman in a patriarchal culture.

Across generations and different phases of life, they carry the guilt of not living up to expectations or failing siblings. The title La otra mamá — The Other Mother — is something that, as an eldest daughter, is hard to let go of. Putting yourself first after a life of putting others first is difficult. But if you take care of everyone, who’s going to take care of you?